Comfort and Ingenuity: Thomas E. Warren

One of the most charming things, I think, is the enthusiasm of American designers after the “Industrial Age” kicked off in the early- to mid-1800s. The phenomenon led to the mass-production of many every-day things, including furniture. Unfortunately, it also led to the mass-production of crap. The rapid mass-production in factories of everything from furniture to vases is what encouraged the rise of the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 1800s.

The Arts and Crafts movement was appalled by mass-production and wanted artists to get back into designing and creating their own works, including furniture. That being said (and don’t shoot me now) I find this chair strangely elegant, if notwithstanding, very uncomfortable. (Added note: what’s with the wheels on late 1800s furniture? Answer: convenience and mass production. It allowed increasingly busy people to move furniture from one room to another without having to buy sets of furniture for each room!)

|

| Thomas E. Warren (1808–?, designer, United States); and American Chair Company (1826–1958, Troy, NY, maker), Centripetal Spring Chair, ca. 1849–1858. Cast-iron, wood, modern upholstery and trim, original fringe, 34 ¼" x 23 ½" x 28 ¼" (87 x 59.7 x 71.8 cm). © Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-3500) |

I’ve talked about the history of furniture before in this blog, and how it historically accommodated the various changes in how human beings are comfortable. During the mid- to late 1800s, comfort sometimes went out the window when design was emphasized. However, this chair, designed as an office chair, bucked the trend while highlighting American ingenuity.

Cast-iron has been around since ancient times, but was only exploited in a major way for design purposes starting in the late 1700s, an example of which is the Severn River bridge in Coalbrookdale, Britain. Learn more about this bridge in my post A Look at Bridges.

|

| Thomas Pritchard (1723–1777) and Abraham Darby III (1750–1789), The Iron Bridge, Coalbrookdale, Britain, 1776–1779. Photo © Davis Art Images. (8S-23663) |

Cast-iron revolutionized architecture, because slender cast-iron columns allowed for larger windows and less massive masonry in high-rise buildings. Starting in the US, it led to the rapid development of the “skyscraper”. It also allowed for decorative building facades that were less ponderous and cheaper than stone and brick examples.

|

| John Gaynor (1826–1889, United States), Haughwout Building, 1856–1857, New York. Photo © Davis Art Images. (8S-14372) |

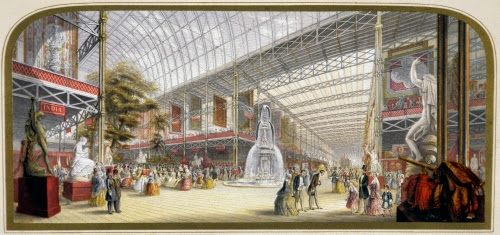

The Centripetal Office Chair was exhibited in 1851 at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry in London in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. The building itself was a bold design of cast-iron and glass.

|

| George Baxter (1804–1867, Britain), The Great Exhibition (at the Crystal Palace), 1851. Etching, aquatint with hand coloring, 6 5/16” x 13” (16 x 33 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2153) |

The chair was hailed as a great modern use of industrial knowledge, considering that the springs were modeled on those of the undercarriages of railroad cars. It is actually symbolic of the start of the aesthetic of modern American office furniture. However, it found little success (sales-wise outside the US) after the Great Exhibition, because it was deemed “too comfortable” for a “proper” office atmosphere. I find it fascinating that Warren based his design on railroad car technology, and then thought to “fancy” it up with lavish upholstery, and a decorative fringe to hide the cast-iron steel support. The curvy cast-iron framework is grounded in the Rococo Revival style that was huge between the 1850s and 1860s.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 6.35, Explorations in Art Grade 4: 3.15-16, The Visual Experience 12.4, Discovering Art History 2.2

Comments