The Beauty of Wayō Shodō

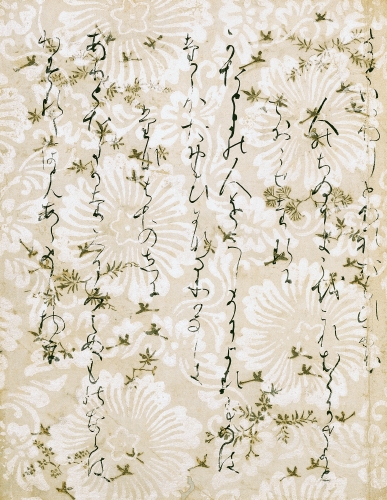

Did you known that the Japanese did not have a written language up until the 400s CE? I find cursive Japanese so incredibly beautiful. The story behind its development is very interesting, and I bet you can’t take your eyes off of this page from a collection of poems! The chrysanthemum design is a woodblock print in white ink infused with ground mica, which sparkles (you can’t really make that out in a photograph). So sumptuous!

|

| Unknown Artist, Japan, Page containing a calligraphy of a poem by Lady Ise (875–938 CE), from a portfolio Anthology of Thirty-Six Poets,” 1108–1112. Ink, silver ink, and ground mica-infused white ink on paper, mounted in 1929 as a hanging scroll, 8" x 6 1/4" (20.3 x 15.9 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2816A) |

In 784 CE the Japanese emperor Kammu (737–806 CE) moved the capital from Nara to Kyoto in order to escape the constant interference of the Buddhist monks in Nara, and establish a strong centralized government based on Chinese models. Within 100 years of the move, official embassies to China ceased because of political turmoil there. Without the dominance of Chinese artistic models, Japanese culture thrived in the wealthy imperial court in Kyoto, ushering in a period of literary, artistic, and architectural flourishing. The dedicated patronage of aristocrats in the court encouraged the development of indigenous religious and nascent secular art.

The Heian period was also a period that saw a rise of provincial military clans organized in a feudal system. These clans continually challenged the emperor’s power and insisted that Japan reject the overwhelming amount of Chinese influence on Japanese culture. The first important novel in world literature, the Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, appeared during the Heian era. Despite constant political turmoil during the Heian Period, it is considered the period during which the foundational classics of Japanese painting, literature, and sculpture were produced.

From the 400s to 700s CE, the Japanese began to incorporate Chinese characters into a written language. Chinese calligraphy at that time was already very advanced. Initially, Japanese calligraphy was called karayō shodō or "Tang (dynasty) style." The oldest extant Japanese script is dated 615 CE, a commentary of the Lotus Sutra composed in standard Chinese script. Although the imperial court in Kyoto encouraged the use of Chinese characters in literature and official documents, by the end of the Heian period, the wayō shodō— Japanese style—was already developing.

The period of the late 800s through the 900s is sometimes called the era of the Three Brushes, named for three prominent calligraphers who helped shape the Japanese style. Of the three, the contributions of Ono no Kichikaze (894–966) are considered the most important, and he is thought to be the first person to form a truly unique Japanese style. The Japanese cursive style was a natural result of the increasing need of artistic expression in calligraphy that would accompany gestural landscape paintings in poems. Like the Chinese painters of landscapes, landscape artists modeled their brush strokes on calligraphy brush strokes.

The script of this poem is the wayō shadō, a style developed at the imperial court. The poem by a woman of the court is thought to have been commissioned for the sixtieth birthday of the Emperor Shirakawa (1053–1129) in 1112. This poem leaf was separated from a collection of some 190 pages of poems, written on paper that was sumptuously decorated with woodblock printed chrysanthemum flowers in white ink made of shimmering ground mica. Additionally, there are pages with pine branches, bell flowers, maple leaves, and birds stenciled in silver leaf. The anthology of poems was executed by twenty of the leading calligraphers of the period. Such luxurious collections of writings are typical of the aesthetic heights that the Heian period art reached.

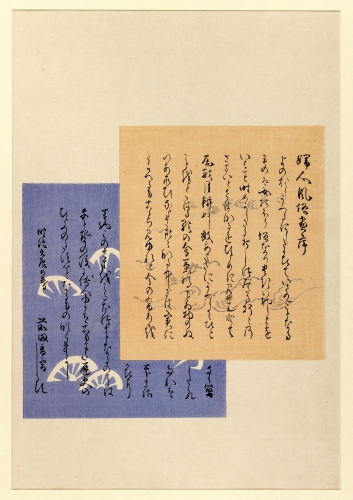

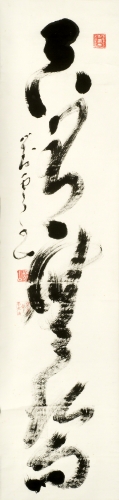

Two other examples of the Japanese cursive style of calligraphy:

|

| Ogata Gekko (1859–1920), Index from the portfolio Women’s Customs and Manners, 1897. Color woodcut on paper, 14" x 9 15/16" (35.6 x 25.2 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2373). |

|

| Hashimoto Dokuzan (1868-1939), Calligraphy of Freely Having Nothing is My Poem. Ink on paper, hanging scroll, 53 5/8" x 13 1/8" (136.2 x 33.3 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-4664) |

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 2: 4.24; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 3.18; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 5.26; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 5.27; A Global Pursuit: 7.5; A Personal Journey: 4.2; Discovering Art History: 4.4; Exploring Visual Design: 1; The Visual Experience: 3.4, 13.5

Comments