A Neglected Japanese Printmaker: Gosōtei Hirosada

I’m pretty sure there’s generally a misconception about the ukiyo-e phenomenon in Japanese art. It is certainly one I had until I recently came across hundreds of gorgeous woodblock prints by a relatively obscure ukiyo-e artist. The misconception, my misconception, is that the ukiyo-e style was an Edo (Tokyo) art movement.

The style name, “pictures of the floating world,” refers to the transient pleasures of life, primarily those in the pleasure districts (Yoshiwara) of cities. This was where Kabuki theater, brothels, restaurants with Geisha entertainment, and fancy teahouses were located. I never thought about the fact that most Japanese cities probably had Yoshiwara and, thus, the appeal of documenting the glittering fashions and events of those locales in multiple-woodblock prints. I have subsequently learned about the thriving print scene in the city of Osaka, and its active theater district, of which Hirosada was a major player.

|

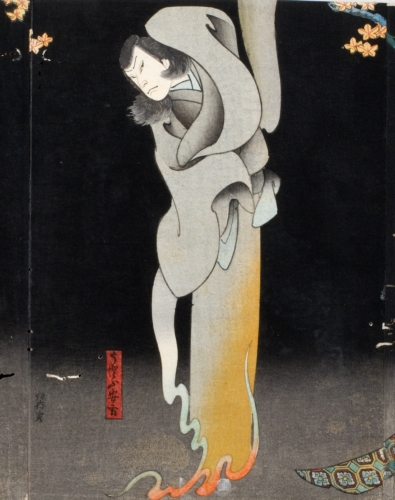

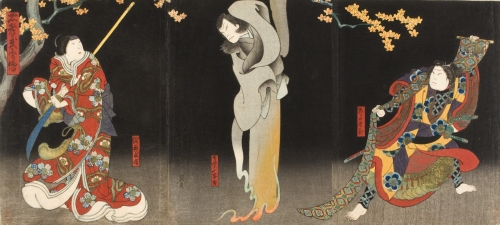

| Gosōtei Hirosada (ca. 1819–1864, Japan), Middle sheet of triptych: Onoe Tamizō as Soma Tarō (right), Arashi Rikaku II as UtōYasukata (center), and Mimasu Daigorō IV as Takeichi Buemon (left) from the Play “The Story of Tarō, Scion of the Soma Clan,” in the Wakadayu Theater in Osaka, 1850. Color woodcut triptych on paper, 9 13/16" x 20 15/16" (24.8 x 53.4 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-5816) |

|

| Gosōtei Hirosada, Onoe Tamizō as Soma Tarō (right), Arashi Rikaku II as UtōYasukata (center), and Mimasu Daigorō IV as Takeichi Buemon (left) from the Play “The Story of Tarō, Scion of the Soma Clan,” in the Wakadayu Theater in Osaka, 1850. Color woodcut triptych on paper, 9 13/16" x 20 15/16" (24.8 x 53.4 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-5466) |

There is no doubt that in the ukiyo-e genre of printmaking, Edo (Tokyo) set the fashion not only in subject matter, but also stylistically starting in the late 1700s. Prints of the Kabuki theater evolved at that time, popularized by Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769–1825), who is equally famous for his actor portraits and interior views of Kabuki theaters. Toyokuni I established the Utagawa “school,” literally artists schooled by him who later adopted his surname Utagawa. These artists included the famous landscape artist Hiroshige (1797–1858), Kuniyoshi (1797–1861), and Kunisada (1786–1864, who also went by the moniker Toyokuni III). Many Osaka print artists studied under the Utagawa artists, and transmitted the fervor for Kabuki prints to that city from Edo. Notable aspects from Edo prints were the oban format (large prints), triptychs of actors set against theatrical backgrounds, and the large head prints (okubi-e). Within these Edo stylistic traits, however, the Osaka prints have a certain provincialism that informs the drawing style composition. Additionally, Edo prints were home of the aggressive Kabuki style (aragato, or, wild acting), which stressed universal ideas of heroism, fighting and display. I think this Kunisada aptly demonstrates that preference.

|

| Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III, 1786–1864, Japan), Ichikawa Danjūrō as Unno Kotarō Yukjuji (Disguised as Yamagatsu Buō) in the play “The Barrier Gate” at the Ichimuraza Theater in Edo, 1828. Color woodcut on paper, 8 1/4" x 7 7/16" (21 x 18.9 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2671) |

Osaka artists preferred the wagoto style, which emphasized speech and gesture. It was a more thoughtful and self-effacing style, which focused on individual human interaction rather than bombastic universal concepts. Little is known about Hirosada, save that he is thought to have apprenticed to an Utagawa school artist of Osaka, and studied alongside that artist in Edo with Kunisada. Hirosada is undoubtedly the most prolific of the ukiyo-e print artists during the late flourishing of the art, which took place after the Tenpo Reforms of 1842, morals laws that banned Kabuki theater and prostitution and prints of those pleasures. By 1847 the laws had relaxed, but many artists, like Hirosada, started the practice of making exclusive sets of prints for discriminating clients. The prints from this period were jewel-like, printed in bright, enamel-like colors on thick paper.

Hirosada pioneered formats in Osaka such as the triptychs of large head prints, in which the characters interact with one another as they do the full-length characters in triptychs. Look at the gorgeous color in the ghost scene above. It is conceivable that Hirosada obtained his format of large head prints from Kunisada, but his prints are much more mannered, and the drawing is a little less sophisticated in the features. I am no expert on the subject, but I have never seen a large head print from the ukiyo-e genre in which the figure busts the picture plane as the actor does in the center of this large head triptych. Don’t even ask me how that is achieved.

|

| Gosōtei Hirosada, Nakamura Tomijurō II as Toki Hime (right), Onoe Tamizō II as Sasaki Takatsuna (center), and Arash Rikaku II as Miuranosuke (left) in the Play “A Chronicle of Three Generations in Kamakura” at the Minami Theater in Kyoto, 1849. Color woodcut triptych, 9 3/4" x 20 15/16" (24.8 x 53.4 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA-5610) |

Hirosada’s work is a wonderful example of the last flourishing of a remarkable genre of printmaking lasting from the late 1840s to the late 1860s. The Osaka school of printmaking never really achieved such a rich and vibrant school of prints during the Meiji period (1868–1912), and it certainly never attained a greater print artist than Hirosada.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 1: 2.9; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 1.3; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 1.2, 1.1-2 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 1.4; Explorations in Art Grade 6: 1.1, 1.4, 1.1-2 studio; A Personal Journey 1.3, 4.2; A Community Connection: 8.2; A Global Pursuit: 7.5; Experience Printmaking: 3, 4; Exploring Visual Design: 1, 12; The Visual Experience: 3.5, 9.4, 9.12, 13.5; Discovering Art History: 2.2, 4.4

Comments