Not Quite Bedhead, But...

Yesterday I woke up with a terrible case of “bedhead.” My hair seriously looked like it used to in the late 80s when I purposely got it to look that way with a can of Aquanet. That got me to thinking about the many busted hairdos of history that I’ve seen in works of art. Let’s subtitle this week’s posting “tidbits of fashion history—hairdos.”

|

| Ancient Egypt, Head from a Female Sphinx, ca. 1876–1842 BCE. Schist, 15 5/16" x 13 1/8" x 13 15/16" (38.9 x 33.3 x 35.4 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-1147) |

I know that the Egyptians shaved their heads because of the heat and wore wigs on special occasions. Although, I think a buzzed head is cooler than a wig. Just my opinion. What’s interesting about this beautiful sculpture is that this artist chose to make sure no one would wonder if this was a wig an Egyptian woman would wear on this semi-divine creature. Sphinxes were traditionally lion bodies with a human, often female head. This one seems like a portrait. Her wig reminds me of how big my mother’s hair used to be in the mid-1970s.

|

| Ancient Rome, Portrait Head of a Woman, 100–125 CE. Marble, height: 13 3/4" (35 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-552) |

This hairdo appears on many portraits of wealthy Roman women during the Trajan-Hadrian era on ancient Rome (ca. 98–138 CE). For such an idealized face on this woman, the artists certainly took pains to reproduce her curls. I can’t even imagine how much work this look took every morning, or, perhaps, this style was reserved for special occasions. Flavian hairstyles such as this were achieved with padding and artificial curls to create height. The writer Juvenal (60–130 CE) commented that Roman women looked tall from the front but short from behind.

|

| Pakistan, Bust of a Bodhisattva, 100s–300s CE. Gray schist, 28 3/8" x 19 3/4" x 8 1/4" (72.073 x 50.17 x 20.95 cm). © Dallas Museum of Art. (DMA-20) |

After Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE, his conquests of Asia disintegrated into numerous contentious petty kingdoms run by his erstwhile generals. The Romans took over Alexander’s conquests eventually, establishing trade with China via the Silk Road that ran north of India/Pakistan. Indian artists were exposed to Greco-Roman sculpture that influenced some of the (thought-to-be) earliest images of the Buddha with decidedly Greek influence. I’m fascinated by this artist’s interpretation of Greek curls. I’m wondering if it was under the influence of Greek sculpture that the “ushnisha” (or “topknot”) came about in depictions of the Buddha, since it was never mentioned in accounts of his physical appearance. The ushnisha came to be a symbol of Buddha’s reliance on the spirit.

|

| Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464, Flanders). Madonna and Child, ca. 1454–1464. Oil on wood, 12 9/16" x 9" (32 x 23 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (MFH-10) |

Even though religion usually focuses on the life of the spirit, it’s amazing the visual symbols artists had to resort to in order to put a point across when realism was a concern. Rogier van der Weyden was one of the masters of the Northern Renaissance, where artists were the first in Europe to prefer oil paint to tempera. What’s compelling in his depictions of the Madonna is representing the medieval idea that a high forehead indicated wisdom. Apparently, some women at the time shaved their hairline back to look more “thoughty.” I doubt such a trend would catch on nowadays.

|

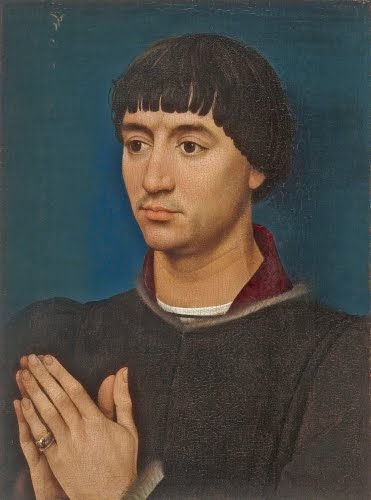

| Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464, Flanders), Portrait of Jean Gros, left wing of a diptych, 1460–1464. Oil on panel, 15 1/8" x 11 3/8" (38.5 x 28.8 cm). © Art Institute of Chicago. (AIC-389) |

And, yes, at the same time, boy bangs were really popular.

|

| Nicholas Hilliard (ca. 1547–1619, Britain), Portrait Miniature of a Woman, ca. 1590–1595. Watercolor on vellum, 2" x 1 5/8" (5 x 4.3 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-1165) |

Queen Elizabeth I (died 1603) of England suffered from smallpox when she was 29. Not only did it damage her skin to the point where she supposedly used makeup of lead mixed with egg white, she also suffered hair loss. She wore wigs of curls exposing a high forehead (no longer, I guess, a sign of wisdom?). Needless to say, the women of her court imitated the fashion, because she was a much beloved ruler.

|

| Jean-Jacques Caffieri (?) (1752–1792, France), Bust of the Sculptor Corneille van Cleve (1646–1732). Marble, height: 27 1/2" (70 cm). © Cleveland Museum of Art. (CM-361) |

Since the 1500s, long hair for men was fashionable. The French powerhouse King Louis XIV (1638–1715) always prized his flowing locks. Unfortunately, starting in 1655, he began losing his mane. Thus was begun a fashion of wigs for men that endured until the late 1700s in Europe, as courtiers adopted wigs to soothe the ruler’s ego. Louis is reported to have hired 48 wig makers for his personal collection. This portrait of the sculptor Corneille van Cleve shows one of the most glamorous styles of men’s wigs. Is this where the term “bigwig” originated?

|

| Joshua Johnson (ca. 1765–1830, US), Portrait of Edward Aisquith, ca. 1810. Oil on canvas, 22 1/2" x 18 3/8" (57.2 x 46.7 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2763) |

During the height of fervor for classicism in the West (ca. 1780s to 1810s), all sorts of fashions were inspired by “antique” dress, including hairdos. Men’s hair was brushed forward to imitate the forehead curls of such ancient greats as Julius Caesar (100–45 BCE). In France the style was called “coups de vent,” literally “blows of the wind,” because, we all know such glamour is achieved merely by walking outdoors on a windy day. Nowadays, a look like this might be mistaken for a combover?

|

| Gosotei Toyokuni II (1777–1835, Japan), Bust Portrait of a Courtesan, late 1820s. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 3/8" x 9 1/2" (36.5 x 24.2 cm). © Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2741) |

During the Edo Period (1615–1868) in Japan, the Ukiyo-e prints chronicled the latest fashions as worn by famous beauties in the entertainment districts of Japanese cities such as Tokyo (Edo) and Osaka. What started in the 1700s as understated elegance in hairpins shown in the work of artists such as Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770) and Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806), by the late Edo period became gaudy and overdone. Note the stunning poise of Gosotei’s model with the weighty hairpins. I especially appreciate the “X” framing her face with the delicately penciled in eyebrow situation. Gosotei was the most prolific and most copied artist of actor and beauty prints from Osaka.

|

| Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806), Shinowara of the Tsuruya House. Color woodcut print on paper, 14 15/16" x 9 13/16" (38 x 25 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-942) |

|

| Paul Delaroche (1797–1856, France), Portrait of Madame de Therville, ca. 1830. Pastel and chalk on paper, 8 5/8" x 8 1/4" (22 x 21 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (MFH-350) |

What succeeded the Neoclassical period was Romanticism. One would think that people would prefer the simple hairstyles of antiquity. But no, hair gradually grew in scale from the 1820s until it reached ridiculous complexity in the 1830s. Notice any similarity to the Flavian woman from Ancient Rome above (well, except for the dour look on this woman’s face)? These styles were often festooned with ribbons and flowers for really special occasions. Again puffs and pads helped achieve these up dos.

|

| Papua New Guinea, Malagan mask, late 1800s. Wood, paint, opercula shells, lime plaster, plant fiber, rattan, 15 1/4" x 9 1/2" x 12" (38.7 x 24.1 x 30.5 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (MFH-614) |

The Malagan was a ceremony to honor a deceased person or spirits of deceased ancestors. “Malagan” refers to both the ceremonies that occur after burial, and the masks, figures, and posts made for us in them. This mask used for the Malagan is called “tatanua” after the dance for which it is used. The mask is danced in pairs or in groups of dancers. The spirit of the deceased was traditionally thought to enter the mask. It is possible that such masks were “portraits” (stylized) of the ideal male. They were meant to honor the deceased, ward of malevolent intentions, and sever the deceased from possessions in the physical world. The feather part of the mask imitates the hairstyle worn by young men for Malagan ceremonies, in which the head was partly shaved and the hair stiffened with lime (healthier than Aquanet?). Learn more in my post from April 21st.

|

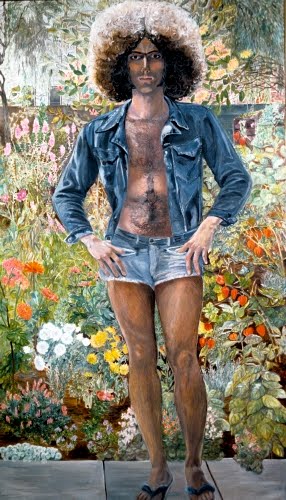

| Sylvia Sleigh (1916–2010, US born Wales), Annunciation: Paul Rosano, 1975. Oil on canvas, 90 3/16" x 51 15/16" (229 x 132 cm). Photo courtesy of the late artist. © 2016 Estate of Sylvia Sleigh. (8S-18364) |

Yes, this hairdo has made a comeback in the 2010s. I love the work of Sylvia Sleigh because she turned the tradition of the “nude” on its head during the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s. Before that time, the word “nude” in art was almost always associated with a female model. Sleigh went one better with her male models—rather than idealizing the nude as was traditional—by delineating every hair on their bodies, if you know what I mean.

|

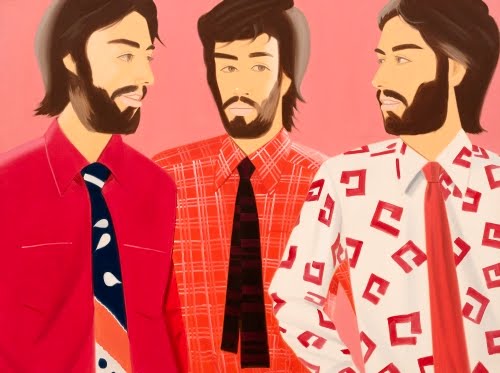

| Alex Katz (born 1927, US), Red Tie, 1979. Oil on canvas, 71 13/16" x 96 1/8" (182.5 x 244.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2016 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (MOMA-P1643kzvg) |

Anyone who lived through the 1970s can appreciate the unique sophistication and elegance of men’s fashions from that period. All I can say about this painting is that at least they don’t have lumberjack beards and man buns.

|

| Speaking of glamour, poise, and sophistication, this is what the well-groomed art historian with an MA did with his hairdo in the mid-1980s. And yes, I did go to work on the subway in Chicago everyday looking like this! |

Comments